Joe's Story - February 2002

The next and final trip almost proved to be my undoing. Danny was

supposed to be on this trip across the Copland Pass with me, but he

very wisely pyked to avoid an almost certain death. The Copland Pass

is a bottom-end mountaineering trip with a traverse down a steep

glacier which is fully bergschrunded and crevassed. It is a daunting

prospect for a tramper, especially for someone travelling from the

west-east direction which added 1,000m of climb to the trip and

potentially fatal navigational booby traps.

The first lag was an easy 4-hours into Welcome Flat. This is a

magical spot right under the Sierra Range which towered more than

2,000m above and spilled glaciers from the skies. And what's more,

there are natural thermal springs right there amidst the alpine

grandeur! I spent about an hour and a half in the hot pools chatting

with some American mountaineers who tried for Copland Pass but got

to Fitzgerald Pass instead and almost killed themselves. That was a

great confidence booster of course. After dinner I couldn't bear

going to sleep when the stars were out in force shinning at us, so I

just sat around the hut admiring them and tried to learn Dutch and

improve my German. I will have some animals to play with when I visit

Europe next year as the chief scientist of the Dutch national wildlife

reserve took a rather strong liking of me. We stayed up and chatted

until well past 1 a.m. about life and all that general guff.

This almost proved fatal. Due to very little sleep in the last two

days and the tranquillity of the bivvy, I woke up very late and

didn't get going until 12:30pm the next day. In sweltering heat, I

did not make the 1,800m climb up to Copland Pass until after sunset

when the Copland snowfield froze. This was a very bad place to be at

a really bad time. I made a difficult decision to descend the eastern

ice face in semi-darkness, on my own and without mountaineer equipment

except my ice axes and crampons. Were the situation to arise once

again, I think I would still make same decision. But it was just a

most imbecilic thing to be on Copland Pass at that time of the day,

something I hope I'll never be stupid enough to do again.

I can only say I am lucky to be alive. Half way down the ice face

as I was front-pointing down (which I hadn't done for 6 years since

I learned it), one of my crampons slipped because my boots were

disintegrating and my soles were splitting apart. How I got out of

that one alive I don't know, except I somehow half-fell down the

vertical ice face into a crevasse where I adjusted the crampons.

Further down the snowfield I slipped and fell for about 7 metres.

Now I have not done any self-arresting ever since I learnt it in

beginners' snowskool in 1996. I had no chance to practice it and

only rehearsed it in my mind. However, my survival instinct kicked in

and I did a perfect self-arrest. I was in a mental state where the

only thing that concerned me was survival, I anticipated the fall to

happen and I took no prisoners in executing the self-arrest. Just as

well. Another 10 metres further down would have been a vertical ice

face with a series of crevasses which would have certainly proven to

be my grave.

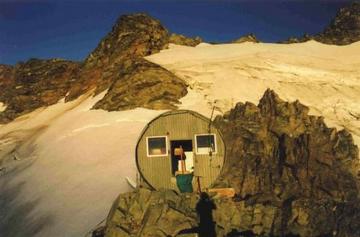

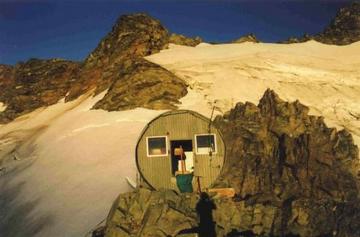

It must have been about 10:30 or 11:00pm when I left the last patch of

ice and climbed the rocks to Copland Bivvy in almost pitch darkness.

Every step in the last hour was knocking on death's door, and had

I died there, I would simply have been a missing person as no one

knew where I was. By the time I reached the beloved Copland Bivvy I

was completely exhausted, mentally and physically, with ~11 hours of

tramping that day, 1,800m ascent up treacherous rotten rocks on the

west with a heavy pack, 250m of front-pointing down a glacier and two

near-death episodes. I was in full crisis-management mode on the

glacier, just being completely logical, calm, concentrating on every

move down the ice, appraising my situation constantly and keeping

emotions completely out. But when I reached the bivvy, I laid in a

heap on the bivvy floor shaking uncontrollably for a long while before

gathering enough strength to cook dinner. This is an experience I

never want to repeat again, and it has inspired me to learn more

mountaineering so I am more apt to deal with alpine situations.

After dinner I sat in front of the Bivvy, staring Mt. Cook who

stood silently across the mighty Hooker Glacier, her snow-capped

summit and glaciers glistening under the midnight moonlight. It was

an absolutely magical spot and I was just speechless. There are

glaciers, ice, snow and moraine coming at me from left right and

centre. It's absolutely indescribable. I was just in constant awe

of the majesty engulfing me. I would still prefer the wilderness of

Fjordland to Mt. Cook, but it was just such an overwhelming sight and

I had photos of Mt. Cook in every mood - first ray of sun rise on

the summit, last ray of sun set on the summit, against cloudless sky,

against amazing cloud formations, in darkness against a multitude of

stars, against fiery clouds foreshadowing an impending storm. It was

a foreign but mind-blowing place, and completely inspiring.

Comparing my ordeal down the icefield, the treacherous Copland Spur

was faint in comparison and I made it down the daunting Hooker moraine

wall without too much hassle, although I could see why many people

would break down and cry. There were many moments when I wondered how

I was going to get down alive, but I eventually found a way, and the

Hooker Glacier was pretty easy to negotiate.

Note by Danny: having gone around the Southern Alps the long way

(by bus, via Haast Pass and Wanaka), I ran

into Joe at Mount Cook, on the morning after his trip.

|

Route Description (West to East)

All the route descriptions I have gathered so far have been from Mt. Cook

Village to West Coast. The hut books in the area confirm this: there

are scarcely any successful crossings west to east. If you can, do it

east to west - not only do you save navigation hassles and 1000m of

climbing, but you also get a hot spring at the end and 40 backpackers

marvelling at your staunchness. However, if you HAVE to do it west to

east, I believe these notes will be quite useful. If you survive

without injuries, you will not regret having done the route.

Bring an ice axe and crampons, and know how to use them. Rope and

glacier extraction gear are recommended if you can be bothered carrying them.

- Highway to Welcome Flat: This is straight forward, albeit with some

avalanche spots in winter. Average time is between 4-6 hours. If you

can't do it under 6 hours, question your fitness for the day ahead.

- Welcome Flat Hut: Warning for those who do not like crowds: the hut is

very popular during summer, full every night with 30-50 backpackers who

come in for a night in the hotpools. However the nearby bivvy provides

cool and quiet accommodation, if you can put up with the sandflies and

possums.

- Welcome Flat Hut to Douglas Rock Hut: Straight forward track, but

during times of extreme heavy snow this route can have avalanches.

Beyond Douglas Rock Hut the route is constantly swept by avalanches.

- Douglas Rock Hut to Copland Pass: The route is well marked by cairns

as it sidles up the side of Copland Valley. However, after it climbs

up past a gorged waterfall and leaves the main Copland Valley into the

side basin below Copland and Fitzgerald Passes, the cairns disappear and

navigation becomes difficult in times of poor visibility, which is quite

a common phenomenon.

Suitable campsites in the side basin can be found. One is about 100m

about the waterfall in the gorge. Soon above the waterfall, the

snowgrass fields disappear and the ground is very rocky with broken

schist everywhere in summer (and of course blancket of snow and

avalanche debris in winter). However, there are a couple of suitable

campsites further up, at the lower end of a couple of large snowfields

where small patches of flat sandy ground could be found and you can melt

snow for water. The last such suitable place is about 300m below the pass.

The biggest pitfall crossing west-east is navigation up to the Pass.

The problem is avoiding getting to Fitzgerald Pass. Fitzgerald Pass and

the little pass 300m north-west of it (737239) look much more like

passes from the west but should be avoided. There has been several

fatalities in the area, as Fitzgerald Pass is impassable without full

alpine climbing gear and even experienced climbers have difficulty

descending it. There are false cairns leading up to both these (im)passes.

Copland Pass does not look like a pass: it is not the lowest point on the

Main Divide. Instead, it consists of several gaps in the jagged sky

line north of the little pass at 757239. Aim for one of these gaps up

very eroded and treacherous schist. You will be rewarded by a

magnificent view of Mt. Cook when you gain the pass.

- Copland Pass to Copland Shelter: This section is most interesting in

late season (February) as the snowfield consolidates into hard ice and

crevasses open up. As there is no avalanche danger, doing this section

in mid afternoon will increase the chance of finding some soft snow

under your crampons.

Find a suitable place to gain the Copland snowfield. This is easier

said than done. Large burgschrunds run across the snowfield and if you

fall in without glacier extraction equipment you can be in for some

serious trouble. Once on the snowfield, there is a rocky spur on your

right (south), linking the Main Divide to Hooker Morraine Wall. We'll

call this the Copland Spur. Look for Copland Shelter: it should 200

metres below on Copland Spur, with conspicuous orange paint. If you

cannot see the Shelter and you are on 70 degree vertical ice, ponder on

your navigation.

The way down to the Shelter is on the snowfield next to Copland Spur.

On the flat top of the snowfield, walk south and approach the spur.

Then proceed down on the snowfield, front-pointing, negotiating

crevasses. After 200 metres, the spur flattens and is covered by snow.

Walk on the snow-covered spur towards the Shelter, crossing over to

the Fitzgerald side. Walk on the edge of the snow until you hop off the

snow up to the Shelter which is a welcome relief and a fantastic place

to contemplate life under awe-inspiring Mt. Cook.

- Copland Shelter to Hooker Glacier: Do NOT attempt to cross the gut on

the right under Fitzgerald Pass to gain Hooker Hut. There has been a

landslide in the gut and every year several people break a few limbs

trying to negotiate the gut. Do not attempt the gut on the left under

Copland Pass either - you'll understand why when you get there. The way

to go is to stay on the very tip of the ridge all the way down to the

Hooker Glacier morraine wall. It may seem impossible and sometimes it

is tempting to stray towards guts on boths sides. But yes, it is

possible, and staying on top is the only way.

Once on Hooker morraine wall, look for cairns on the northern side,

close to the gut draining Copland Pass. I did not find the morraine

wall too bad, although some climbers tell of stories of people breaking

down crying on the Hooker and Tasman morraine walls.

- Hooker Glacier to Mt. Cook Village: The Hooker Glacier is

covered in morraine at this point and is a stroll in the park to negotiate

compared to your last few hours. Occassionally giant crevasses remind

you that you are actually on a glacier. Walk on the glacier, stay close

to the west side under the western morraine wall, go around Lake Hooker,

and eventually pick up the tourist trail. Most streams on the western

side disappear underground by the time they reach the glacier level.

However, Eugenie Stream is impassable after rain or high snow melt.

Go after your dreams!

|