Paris has been radically reallocating space from motor vehicles to cycling and public space. The most visible changes are the dramatic cycle tracks (Rue du Rivoli, etc) and the space reallocation (Place de la Bastille, etc). But there are less visible changes that are just as important, in particular low traffic streets and circulation system changes. And the political and legal and design context of these changes is important.

cycle tracks

The cycle track along Rue la Fayette had only just opened, but is already well used - this photo was taken in mid-afternoon, not in a commute peak.

And here's a photo of Rue du Rivoli. Note the direction of the cycle symbols: I am in a 5 metre wide one-way track, the cycle track the other way is the other side of the street-sweeper! (This section is still very temporary and I assume a proper rebuild will reallocate some of this space to widening the footways.)

Paris' cycle tracks are almost all "on carriageway" but separated from motor traffic by kerbing. These kerbs are granite (for heritage reasons) and in some places a good 20cm high but elsewhere only 5cm high (so fire engines can overrun them).

We saw some painted on-footway cycle tracks which are distinctly less functional; these appear to have been an emergency Covid response, now deprecated. [Update: I'm told that the lanes in my photograph were introduced pre-Covid, through a participatory budgeting process.]

Minor road entries are mostly signalised (unlike in the UK), but there are "cycles yield on red" signs which allow people on the main road to cycle (in some directions) through red lights while giving way to cross traffic. This makes them less disruptive of cycling than might be expected.

A lot of the cycle tracks are two-way. Some of the common problems of these are avoided because 1) the tracks are so long that transition problems at their ends are a relatively minor concern and 2) the prevalence of signals (feux) at minor road junctions makes movement between the cycle track and the "other" side of the road relatively easy. But it does complicate interactions at junctions.

There are also some effective rues velos ("cycle streets"). Note the distrinctive think yellow edging.

junctions

Major junctions are a mixed bag: some have proper protected cycle movements, others don't. On our first day (coming back from the 15th) we went through some fairly hairy intersections where we had to make unprotected left turns across two-way motor traffic.

The most dramatic changes have been the conversion of roundabouts to U-shaped two-way roads, allowing not just cycling infrastructure but reallocation of space to public realm. At Place de Catalogne, huge expanses of asphalt have been replaced with an "urban forest". Place Bastille and Place de la République now have large areas of public space.

At Place Bastille there are signalled cycle crossings, but having the cycle tracks directly abut the carriageway means these involve right-angle turns and lack space for cycles to wait without blocking traffic. The cycling provision at Place de Catalogne was only just being finished, but the setbacks seem insufficient, especially for a two-way cycle track.

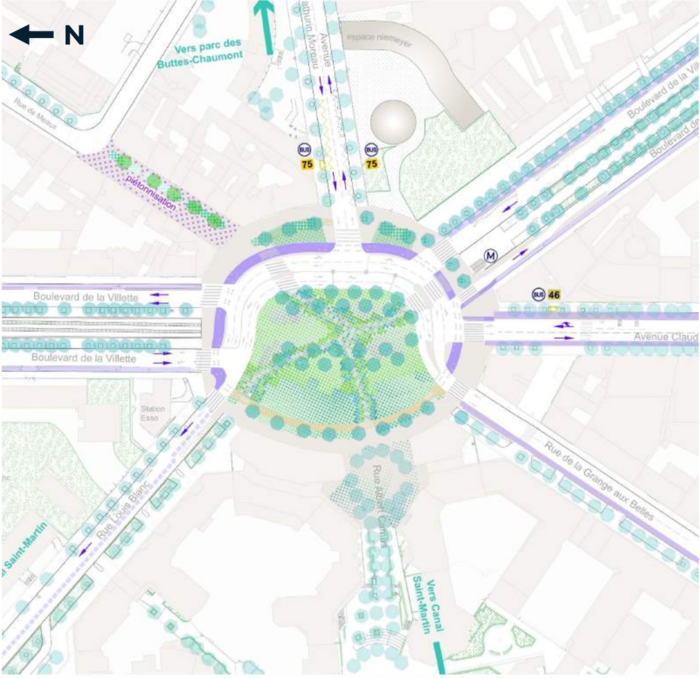

And the plans for Place du Colonel Fabien (where we were staying) look like they risk replicating some of these problems, with a two-way cycle track around the "U" with no separation from the carriageway. I can understand the desire to transfer as much space as possible to public realm, but these roundabout conversions need to provide buffering between the cycle tracks and the carriageway, have cycle tracks approaching crossings at right-angles to the motor traffic flows, with setbacks and clear visibility, and provide space for people cycling to wait for signals. (Some of these designs seem like they were done by planners who don't understand cycling and have just been told that 4 metres is a good width for a two-way cycle track.)

On the other hand, this would still be a big improvement on the current situation: Place du Colonel Fabien currently makes Oxford's Plain roundabout seem cycle-friendly!

But in many ways the things one can't see are just as significant: all the cars, parking spaces and traffic lanes that are no longer there.

rues apaisées - low traffic neighbourhoods

As in the Netherlands, most streets have been made safe and comfortable to cycle on without any infrastructure per se, by reducing motor traffic volumes. The French call these rues apaisées or "calmed streets", whereas in Britain we call them "low traffic neighbourhoods", but at least in Paris they involve traffic reduction first and foremost, not just traffic calming. (I almost prefer the translation as "peaceful streets", though that makes an interesting contrast to Manchester's "active neighbourhoods".) Along with modal filters, one-way restrictions are widely used. This frees up a lot of space, which is particularly important on civic streets with high pedestrian flows and loading/delivery requirements.

Carriageways are narrow and 30km/hr (20mph) speed limits are nearly universal; there are even some streets with 20km/hr (12mph) speed limits. The Peripherique is 70km/hr (43mph), but there are only a few bits of 50km/hr (30mph) speed limits inside that.

One of my favourite examples of a rue apaisée was Rue de Meaux, which I stumbled over when I went for a walk on my first evening. Apparently this used to carry 6,000 motor vehicles day, now it feels more like 1,000. It is one-way and has two modal filters (one at Place Colonel Fabien and one half-way along), stopping it being used as a through route.

There are some streets calling out for being turned into rues apaisées: Rue Saint Dominique (in the Seventh) may be chic (and its patisseries are excellent), but it would be vastly nicer if it had through traffic restricted (and less on-street parking).

broader circulation/network changes

Returning to where I started, Rue la Fayette used to have two lanes eastbound and two lanes westbound, one of the latter reserved for buses and cycles. It now has one general traffic lane eastbound, one westbound bus lane, and that lovely wide two-way cycle track.

This kind of change seems quite common in Paris: it allows space reallocation without losing bus lanes. (I wonder if something similar couldn't be done on Oxford's Woodstock and Banbury Rds - previously I had ruled out one-way systems for Oxford because of the problems they would create for buses.)

In some case space reallocation has been even more dramatic: what can't be seen in this photo?

parking

Paris has quite radically removed on-street parking. And the combination of enforcement and physical infrastructure seems to keep illegal parking mostly under control (my vague memories of Paris from 25 years ago are that parking used to be completely feral). Bollards are widely deployed along the edges of carriageways to stop pavement parking; with one-way or narrow streets they often make it impossible to park illegally without blocking motor traffic.

There are some parking garages - the ones near Place du Colonel Fabien were about €105/month (one of them had a €31/month option for cargo cycles).

the politics

The Paris city administration has much more power relative to the arrondissements than the London mayor has compared to London boroughs. Paris is the "Highways Authority" and can impose road schemes, though in practice it may allow the arrondissements to veto or initiate projects. The cycling infrastructure and reclamation of space from cars may be better in eastern and central Paris than in the (more affluent) west, but the difference is nothing like that in London between (say) Hackney and Chelsea + Kensington. (The arrondissements are also, on average, a third the size of London boroughs.) So the relationship is more like that of Oxfordshire County Council to the District and City councils.

We didn't get to talk to anyone from the mayor's office on the trip. It would have been interesting to hear from some of the planners and engineers there.

One striking thing about Paris is how fast things have been happening since 2020, in Annie Hidaglo's second term as mayor. Work was still underway along Rue de Meaux, the cycle track on Rue la Fayette had only just opened (Google Maps still had part of it as "under construction"), and there was still fencing at Place de Catalogne. Two of the people on our tour group woke up on their first morning in Paris to find the cycle track being constructed outside their hotel had just opened. When I asked about Place Colonel Fabien, I was shown the plans for a redesign. And so forth. Some of this may be preparation for the Olympics.

One constraint Paris has in common with Oxford and London is that taking space from buses is problematic - and all the cycling infrastructure that has gone in has preserved bus lanes. But Paris has some barriers to putting in infrastructure that neither London nor Oxfordshire face.

The "protectors of patrimony" are architects who can veto any changes within 500 metres of a historical site (which means pretty much all of Paris). This is one reason for the lack of any standard policy on colouring cycle infrastructure, and apparently in one location resulted in an entirely unnecessary cycle track being put in to keep the street symmetrical! In contrast, heritage constraints are significant in both London and Oxford, but tend to apply to building designs rather than to road layouts or appearance.

Some main roads are "owned" by the prefectural police, who can veto any schemes on them (or on streets near their offices). One key example is Boulevard de Sébastapol, where they are holding up plans to widen the clearly inadequate cycle track (which has up to 15,000 cycle movements a day).

Paris does not have the power to use automated number plate recognition to enforce traffic restrictions. Cameras can be used, but fines can only be issued by officers watching the camera feeds. (Until 2022 Oxfordshire had that power only for bus lanes; London boroughs have had it much longer.) This is a major problem with enforcing the Limited Traffic Zone (ZTL) which is supposed be starting this year, preventing through traffic transiting the very centre of the city (roughly the 1st arrondissement). It is also why all the school streets schemes are implemented with "hard" infrastructure.

demographics

The composition of people cycling around Paris seemed very similar to that of Oxford or the Netherlands - a pretty even gender balance, wearing normal clothing, and at all times of day (though with obvious commute peaks). This contrasted with London, which seems (based on my limited experience) to skew more heavily to commuter and delivery cycling, with quite low numbers of people cycling through much of the day. (Paris seemed to have fewer children and people with children cycling than East Oxford, but I may have just missed seeing the school runs.)

The composition of cycle campaigners in Paris is radically different to that of London or Oxford. Oxford transport campaigners used to be male and 50+, but now skew female and 35+; our tour group was similar (about two thirds women). In contrast, the campaigners who welcomed us and showed us around were mostly men, but probably averaged about 25.

One of the big questions/possibilities that I came away with from the trip is how to get that demographic involved in Oxford. In 1998 the Oxford University Students' Union had a Transport Officer, but undergraduates now seem too focused on their studies; graduate students and early career workers are probably more fertile soil.

Guidance and Standards

The official French cycling standards (from Carrera) are dated. Paris en selle has published an excellent Guide des aménagements cyclables (the PDF version is free). This has unfortunately not been translated into English, but is well worth a read if one has some French and/or is happy to use automated translation. It is much more accessible than Dutch guidance, and foregrounds the fundamental points better than than something like the UK's Cycle Infrastructure Design (LTN 1/20).

conclusion

Is it perfect? Obviously not. Paris still lags Dutch cities like Amsterdam by quite some way, and even some new pieces of infrastructure have problems. But things are moving really fast, and cities like London and Berlin are being left way behind.